When I am not at the Free Library of Philadelphia acting as a Teen Programming Specialist, I am usually in a studio somewhere making dances, or rolling on the ground in a park somewhere, thinking about different ways to sense and utilize the connection between various toes and the various pelvic bones to which they relate. In other words, I don’t spend a lot of time on computers and with gadgets outside of work. Whatever “techy-ness” I’ve acquired, I’ve acquired as a function of my job. I am not someone who would have ever identified with being “good at computers,” or “tech savvy,” or even remotely in the loop about the latest and greatest tech trends. When most people were standing in line to get an iPhone 5, I still didn’t even have a smart phone.

Through my work at the library, inspired by the interests and skills of our mentors and participants, I have slowly transformed into someone who is comfortable tinkering, diving into the unknown, and acquiring tech skills as a result of a functional task or goal (as opposed to “for the heck of it,” which unfortunately doesn’t inspire me).

A recent example of this transformation is the way I incorporated stuff I learned on the job into my creative practice. I am part of a long-distance performance collective called Mountain Empire, and in May of 2014 we performed the Telephone Dance Project (TDP) in Philadelphia. TDP turns the game of “telephone” into a long-distance collaboration tool. Collaborators Katie Drake of D.C., Eliza Larson of Massachusetts, Rachel Rugh of Virginia, and me, Barbara Tait of Pennsylvania, create movement material, transcribe it to the page and send it to the next collaborator via snail mail. With each reinterpretation, the movement changes incrementally until it barely resembles the original phrase. The material generated is then used to create an improvisational score directed by a different participant in each performance location. The dance emerges anew each time it is performed: duration, sound/music, and creative choices depend on the specific place and time occupied by the participants.

Mountain Empire Members – Screen shot from a Google Hangout Meeting

In Philly, I was responsible for of all elements of the performance – the costumes, sound, improvisation score*, and the context of the performances (venue, kind of show, etc.). One thing that I find interesting about long-distance collaboration is the question it exposes about community – technology gives us the supposed opportunity for a global community, but how much context is lost when your interactions are primarily digital? For me, building a score is creating the context for an improvisational piece. I wanted to have the audience direct us in some way – I was interested in what choices they would make, and whether being involved would make our process more transparent. Because of my experiences at the Library, there was a clear way to go about this: create an interactive sound score so that audience members could touch something that would trigger a directive sound.

To do this, I used a MaKey MaKey – a microcontroller that allows anything conductive to double as a button on a computer, SCRATCH – a drag-and-drop programming language developed by MIT, and Audacity – free, simple, sound recording and editing software. I asked my collaborators to record themselves giving various directives – “Eliza, MA” (our movement material was broken up and labeled by city), “go faster,” “Katie, Philly,” and “go backwards,” are some examples. Using SCRATCH, I programmed the sound files to play when certain buttons on the keyboard were touched. Then, I used the MaKey MaKey to connect those buttons to foil hands and feet in the performance space. I used hands and feet in an attempt to clarify for the audience how it worked – you have to be touching the foot (to ground you) in order to make sounds by touching the hands.

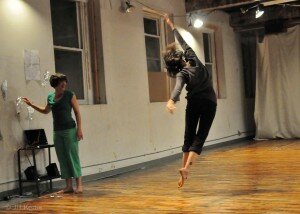

Performer Rachel Rugh (left) beginning the sound directives. Photo credit: Jen Kertis-Veit

Additionally, I built into the score that some of the performers would start touching the buttons first, and invite the audience to join in. Once everyone knew how it worked, the performers re-joined and the audience was in control of the score. Because I was inside the performance, it was hard to tell exactly what was happening – things moved quickly, and I never got a break. But, judging by the number of sound cues and the length of time it lasted, I think audience members found it engaging and exciting. That section of the performance lasted much longer than expected, because people just kept pushing the buttons.

Audience members interacting with the foil buttons. Photo credit: Jen Kertis-Veit

What did I learn from all this? I learned that when it comes to technology, I am inspired to learn only when I have a good reason to learn. As an educator/practitioner, I am always aware of this, but to have the experience of being inspired to use technology in a new way that is personally resonant is a really different thing than knowing it in theory. It reinforces the way we approach learning at the Free Library – to start with each individual’s interests, plant a lot of seeds, and see how you can guide and enrich their trajectories from there.

On a personal note, I also learned that it was fun for me to not know how to do something, and then spend time figuring it out. In the context of technology, this has not ever been the case for me. I get intimidated because I have labeled myself as someone who is a tech dummy, someone who can’t keep up with the flood of information coming at me, and a number of other things. Through engaging with a project that is meaningful to me, all of these assumptions started to fade away, and I was able to be fully present in tinkering. All of a sudden computer programming and other techy activities don’t seem so elusive and intimidating. This is not a small deal; and I am proud to say that our mentors get to be part of this transformation for participants in our programs every day.

*In dance performance, an improvisation score is like the rules to the game. Movement material (for this particular project) was set, but I made rules around how the material was structured, the quality of the movement, and the ways it might be directed by the space, the audience, and/or the sound.